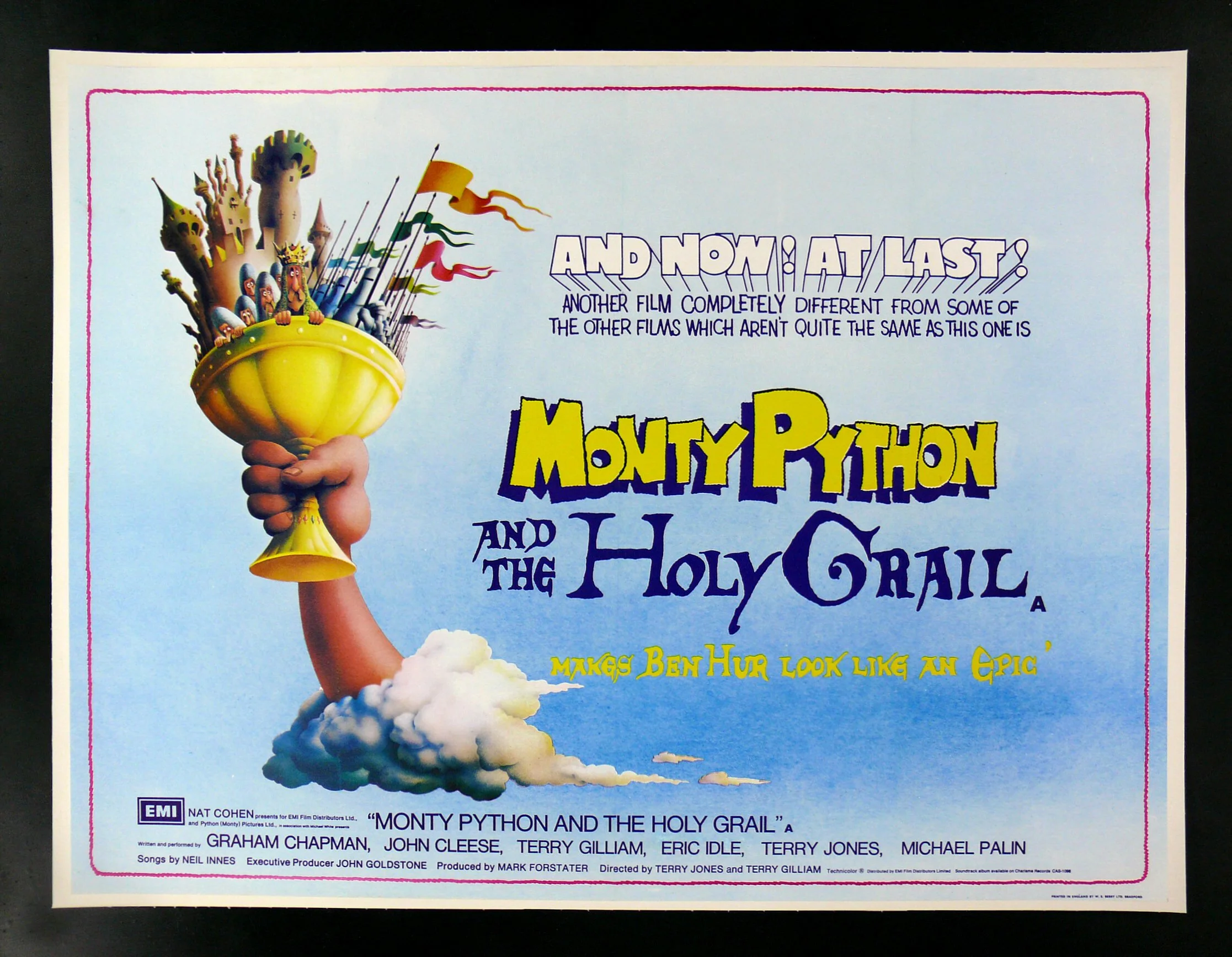

Monty Python Versus the Modern Cinephile

There are two categories of great movies. The first category are movies that are a brilliant demonstration of the director and actors’ craft, their skill at portraying raw emotion and resonant themes that stay with the viewer long after the credits roll. The other type of great movies are films that, regardless of critical acclaim, have gained a loyal and persistent fanbase; in other words, cult classics.

These movies may not be what film buffs like to label as “cinema”, but for one reason or another they’ve inspired hordes of people who would die defending them—e.g. Eraserhead(1997) or The Rocky Horror Picture Show(1975). These movies rarely have anything in common except for a thread of insanity and a refusal to follow traditional cinematic rules. Both these elements are more than apparent in 1975’s Monty Python and the Holy Grail, a comedy written and performed by the sketch group Monty Python.

Uproariously hilarious and ludicrous to a tee, Monty Python was a pioneer in comedy filmmaking, introducing connected sketches as a viable movie format. Their unique humor is so out there that many films have since borrowed its enigmatic formula, including the outrageous History of the World by Mel Gibson. Having seen The Holy Grail when I was younger at the suggestion of my mom, I’ve always been a strong advocate for it. Like many cult followers, I can quote the movie with ease and always enjoy meeting another fan who understands and appreciates my references. In fact, given its age and relative obscurity, quoting Monty Python has become a sort of password into the secret society of fans.

Since the film played such a large role in my childhood, I encouraged some of my uninitiated friends (semi-forcibly) to watch it with me. I cackled through the whole thing, but whenever I looked over toward my friends I saw only vague showings of amusement.

How could I find it so funny while some of my peers found no enjoyment from it. Why were my friends not leaping head first into the cult? To answer this question, one must look at both the movie itself and the modern cultural context it’s being viewed in.

The Holy Grail is not so much a movie as it is a series of vignettes strung along in a semi-organized fashion, vignettes whose narratives are loosely connected by the characters’ quest for the holy grail. The protagonist, King Arthur, spends the first half of the movie recruiting his round table and the second facing foe after foe in accordance with his God-given mission. This plot seems straight forward enough, but it’s about the only form of traditional cinematic storytelling that is present.

Right out of the gate, the movie opens with a set of unusually long satirical credits that spend much of their time crediting “the crew involved with the moose” even though there is in fact no moose in the movie.

From here, it devolves into chaos. Between 3-headed giants and a limbless knight, it’s hard to keep track of the number of perilous and hilarious adventures King Arthur and his merry band go on. But how is this different from other comedies? Why does this style make it a cult worthy movie?

Sketch comedy is fundamentally different from what we may think of as traditional movie comedy. In cinema, comedy is typically situational, and therefore must bend to the will of the plot first and foremost. In short, this traditional form is restrictive. Sketch comedy, on the other hand, has a purity to it; without any obligations to advance the plot, the comedy that is created really knows no bounds. For instance, sketch comedy doesn’t avoid the setting, it changes the setting to fit its will.

Movie comedy lives within the confines of the plot; sketch comedy is the plot. This is how The Holy Grail succeeds in seamlessly combining different vignettes into one film while still retaining a semblance of a storyline. Sure, it may feel disjunct at times, but that's an inevitable and worthy sacrifice. This emphasis on comedy over plot is what makes The Holy Grail stand out. Of course, liking sketch comedy is a personal preference, but I believe there’s more to my friend’s blank faces than that.

Monty Python’s sketch comedy format may have been revolutionary at the time, but the comedy itself is not untraceable. Plenty of movies in the 70s and 80s follow some of the same tropes, including Airplane and The Naked Gun. The outrageous humor and play-on-words style is not uncommon, and funny as it is, it is very different from the popular humor of today.

Movies and stand-up in the modern age often rely on shock humor. As society becomes more “woke”, there are more proverbial pressure points that comedians can target that will elicit laughs from some and offend others. As such, humor has transformed, becoming more about how closely one can get to offending someone while still making them laugh. This is not the comedy of Monty Python, and I think this may be why my friends did not enjoy it as much as I do.

I was introduced to the cult at an early age and was told it was funny and that I should laugh at it. Because I already had an interest in the cult through my parents, it was not hard for me to develop an appreciation for the movie as I grew older. Though I wish my friends could appreciate it, their unmoving faces are a product of their lack of exposure. The ever changing nature of comedy is a trend I simply cannot fight. Some may find the film funny purely based on personality, but I can’t help but lament, the cult of The Holy Grail is slowly disappearing.