Film Melee: Knights, Vikings, & Mythical Adaptations

*Spoiler Warning* for The Northman (2022) & The Green Knight (2021)

To start, I’ll come right out and say it: I love mythology. But lately, I’ve noticed that there seems to be two competing urges at the heart of most mythological cinematic adaptations: preservation and modernization. Countless filmmakers have taken their stab at portraying the tales of ancient European literature on the silver screen, but I’ve seen two recent case studies which best embody these contrasting approaches.

The first is director Robert Eggers’ The Northman. (2022)

Inspired by a 10th century Icelandic work which also inspired Shakespeare’s Hamlet, this tale of vengeance from a boyhood interrupted is familiar to us: prince Amleth (Alexander Skarsgard) must slay his traitorous Uncle Fjolnir (Claes Bang) to avenge the death of his father.

To the uninitiated, The Northman’s blood feud may even seem akin to those of beloved historical works like Braveheart (1995), Spartacus (1960), or Gladiator (2000).

These comparisons are understandable—natural even—and yet fundamentally flawed. I’ll acknowledge an aesthetic similarity in form, but The Northman clearly sets itself apart in function. Anyone familiar with Eggers’ near anthropological depictions of his chosen setting will recognize his newest viking epic as a culmination of sorts; not merely in the ambitious nature of its production, but in the structure of the tale itself.

The Northman captures the habitus of norse culture by unflinchingly conforming to the conventions of traditional Scandinavian sagas. It functions mythologically; not realistically or even heroically. Amleth's narration, often speaking of the looming prescience of fate and destiny, carries forth the straightforward narrative voice heard in runic medieval literature.

The conventions of this 1000-year-old genre are almost never broken; supernatural elements are neither blunted nor explained away by exposition for a modern audience. Sitting in the theater, I remember feeling an uncanny sense that this story was not for us, a sense of bearing witness to a lost tradition.

For example: In any other film, Amleth’s challenge to duel his cursed uncle at the Gates of Hel would be nothing more than a piece of rousing dialogue.

Here, Eggers concretizes these beliefs—smoke, lava, ash and all. Much of the film’s imagery dwells on bringing ritual to life.

Eggers’ forthright depiction of the role played by the supernatural in these sagas, depictions evoking the gods and the acts done in their name, is artful and earnest. Its grandeur is punctuated by the harrowing reality of customs rooted in pillaging, slave trade, and human sacrifice.

Gone is the common modern romanticization of viking culture, and in its absence is we find something raw. Contrasting this preservative approach to mythical adaptation is a legend taken from a different culture.

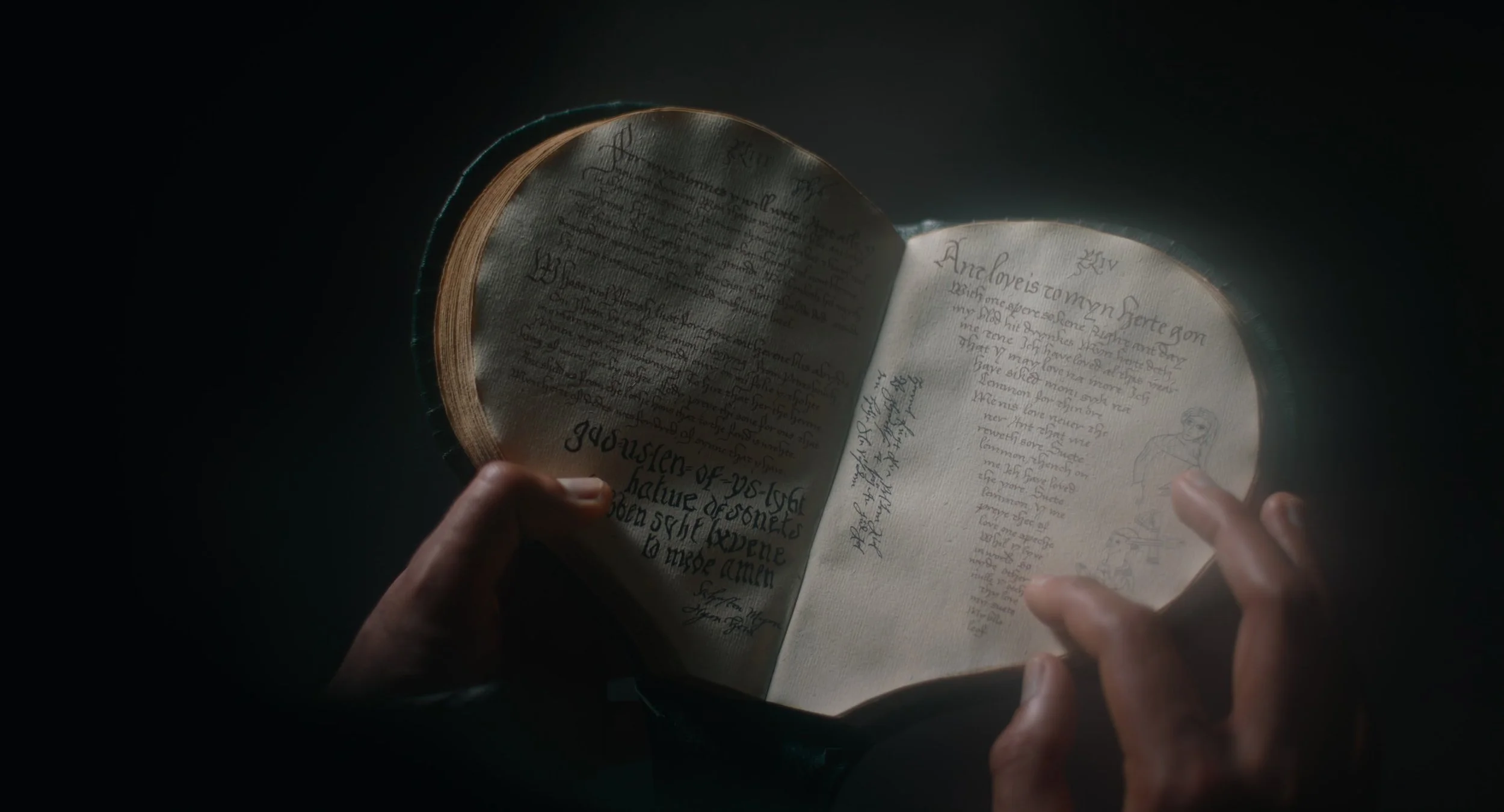

Our next case study is director David Lowry’s The Green Knight(2021).

Based on the 14th century chivalric romance Sir Gawain & The Green Knight, the film’s setup is simple.

A ghostly Green Knight enters the royal court of Camelot to issue a challenge on New Year’s Eve: the knight will allow his opponent to strike him with his own ax, provided that the challenger seeks him out in “one year hence” to receive the same blow in return.

The brazen knight Gawain—nephew to King Arthur—accepts this challenge, beheading this visitor. All are shocked to see the headless Green Knight pick up his lost appendage, reiterate his condition, and take his leave.

The film is quite unconventional. Lowry admits instructing longtime collaborators Daniel Hard and Johnny Marshall—responsible for the score and sound design respectively— to make the tale “feel more like a horror movie.” Consider Lowry’s Camelot: King Arthur and Queen Guinevere are styled as fading monarchs.

Both appear almost ghostly, and their court is shrouded in gray tones and shadows. Gone is the merry splendor of the original poem’s New Years’ feast. It’s safe to say this kind of implied rot, this thematic suspicion of power structures like the monarchy, reflects a modern sensibility.

This choice was deliberate, and I appreciate that. Being a staunch fan of the dulcet unease evoked by many A24 horror flicks, Lowry’s approach certainly caters to my personal aesthetics. Where alarm bells begin to ring is how this willingness to depart from the original poem spills over into the narrative.

Structure is again, significant. Folk motifs commonly found in Arthurian legend remain prominent in the film—e.g. the beheading game and the exchange of winnings.

However, Lowry’s adaptation upends the structure of the original work; what amounts to merely 8 lines in the poem makes up the bulk of the film's visually stunning second act.

I can’t help but question if what we gain in grandeur we lose in nuance. This extended middle leaves the film’s 3rd act much reduced relative to its source material, and in doing so fundamentally alters Gawain’s character arc.

During his voyage, Gawain acquires a green girdle said to protect the wearer from all harm. In the poem Gawain is presented as the most courteous of knights. And yet, Gawain neglects to mention the protective girdle he wears. Though the Knight spares his life, Gawain is shamed by his deception and confronted with an ugly truth. Despite his chivalry, Gawain is mortal— still concerned above all else with his own life. He is made to wear the green girdle henceforth as a brand of his failure.

In contrast, the film affords Gawain a traditional Hero’s Journey. Upon reaching the Green Knight to receive his blows, the capricious layabout we met at the start of the film, now kneels, accepting and unafraid. He removes his green girdle and the screen goes black.

Many label film’s ending as ambiguous, but I’d argue its thematic significance is clear. To embody the hero, Gawain must grimace and bear it. Lowry’s modernized ending is about Gawain stepping into what it means to be a hero, even if it means dying a heroic death. While themes of chivalry, truth, and courtesy are certainly present in the original text, this modern Hero's Journey detracts from the humbling irony of Gawain's fate in the poem.

Regardless, this comparison is not about love or loathing on my part. Both The Northman and The Green Knight make for rich, and most importantly ambitious, additions to the realm of mythological movie adaptations. Both works excite my thirst for what the coming years will bring for this cinematic subgenre.

Cinema is evocative; it’s a cultural conversation. Some would say cinematic retellings of Western myths amount to little more than us talking to ourselves about ourselves.

As we go forward, my truest hope is that producers are as willing to empty their pockets for stories reaped from more foreign waters—And no, schlock like Gods of Egypt(2016) doesn’t count.